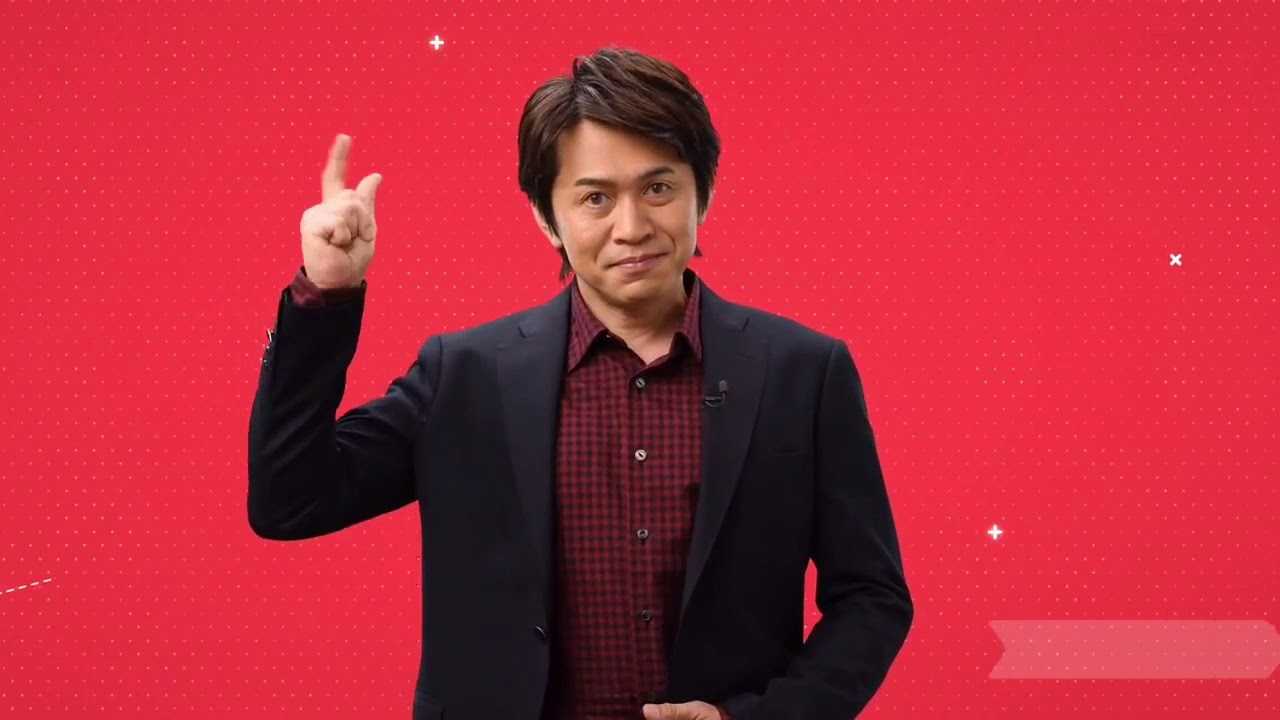

Not only Hideo Kojima: Nintendo also has its “anti-Shigeru Miyamoto” in terms of game design, namely the one and only Yoshiaki Koizumi

Speaking of Hideo Kojima we have defined the visionary as the antithesis of his mentor (declared verbatim as such) Shigeru Miyamoto, but we often tend to forget that even among the pillars of game design of Nintendo itself there is a similar figure: that of Yoshiaki Koizumi. A premise must be made: in theory, Miyamoto prefers to deny the accusations that see him overzealous in putting gameplay first. The master builder of the Grande N has declared himself as not necessarily against a solid plot. And here we are happy to refute such claims as nonsense. With a few exceptions, Miyamoto’s philosophy consists less in “gameplay first” and more in “gameplay only”. And that’s where Koizumi comes in.

There is no Hollywood without screenwriters | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

Born on April 29, 1968 in the Chūbu region of central Japan, Yoshiaki Koizumi receives his first lessons in game design playing Super Mario Bros. 2, to be precise at the age of twenty-one on a borrowed Famicom (from us NES). Graduated from the Department of Visual Conceptual Planning at Osaka University of the Arts, Koizumi specialized in stage acting, film, animation and, albeit to a lesser extent, as a storyboarder. His intention was to become a director (remind you of anyone?) But he joined Nintendo with the aim of pursuing a storytelling only possible in video games. Galeotta, in this sense, was the proximity of the seat to the university!

Back to the past | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

Joining Nintendo in April 1991, Koizumi handled the art, layout and text of the manual for The Legend of Zelda: A Link to The Past. You will remember from our special on the creation of Hyrule the story of the three goddesses. Well, the backstory of A Link to the Past is Koizumi’s bag! As is the plot of another Zelda that the game designer only had to create the manual for, Link’s Awakening. Not only that: the dialogues with the islanders, the owl’s sentences and even the character of the Windfish are his work. An experiment of Koizumi that never came to light, however, was a side-scrolling polygonal remake of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, in which you fight with the rules of chanbara (Nintendo Switch Sports). It is with Super Mario 64 that the partnership with Miyamoto actually begins: with the retouches to the underwater animations of Mario.

Play it again, Link | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

During the development of Super Mario 64, the Big N begins to lay the foundations for a three-dimensional The Legend of Zelda initially more based on puzzles (and on paintings, as the clash with Specter Ganon reminds us). Together with Toru Osawa and Jin Ikeda, Koizumi shapes Ocarina of Time. During the visit to Toei Kyoto Studio Park suggested by Osawa, Koizumi notices during a performance that one of the actors (in the role of ninja) attacked the lead samurai while the others waited their turn. Ocarina of Time’s “almost turn-based” combat, Z-targeting included, was born this way. Meanwhile, Miyamoto has greatly shortened the metaphorical leash of Koizumi, who after the “too strange” story of Link’s Awakening “would never have allowed him again” to do such a thing. And of course, as a storyteller that he is, Koizumi took it all as one compliment!

There is strangeness and strangeness | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

Following Ocarina of Time, Koizumi was reviewing a video game version of cops and robbers. The purpose? Catch the criminal over the course of a week in-game, or an hour in real time. That didn’t come to light either, in favor of aiding in the development of The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. Koizumi kept the idea and, by sheer coincidence, even managed to merge it with another one by Miyamoto. In fact, the latter wanted a replayable Zelda to the bitter end, which is why we owe the moon and the three-day cycle of Termina. True: the gameplay motivated everything, but the hasty development of the game forced Miyamoto to loosen the aforementioned leash. From Eiji Aonuma come the comic moments of the game, and from Koizumi the main plot: realistic and, more often than not, oppressive.

“She’s buried under the tree on that hill!” | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

Not much to say about Donkey Kong: Jungle Beat, outside of a side-scrolling view as a cop-out for the eternal war between 3D platformer and camera. Much more interesting, however, it is Super Mario Galaxy. The plot of the game is very simple: Bowser kidnaps Peach, takes her to the center of the universe and from there intends to exploit the power of the cosmos to dominate creation. However, the reason everyone remembers Galaxy these days (other than sublime level design) is the backstory of Rosalina and the Lumas (which is why the character of Baby Rosalina in Mario Kart 8 Deluxe lacks a bit of sense, ed). How did Koizumi put a story into a Mario game, then? Will Miyamoto like her? In retrospect perhaps yes, given that the latter he didn’t even know!

The galaxy turns for everyone | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

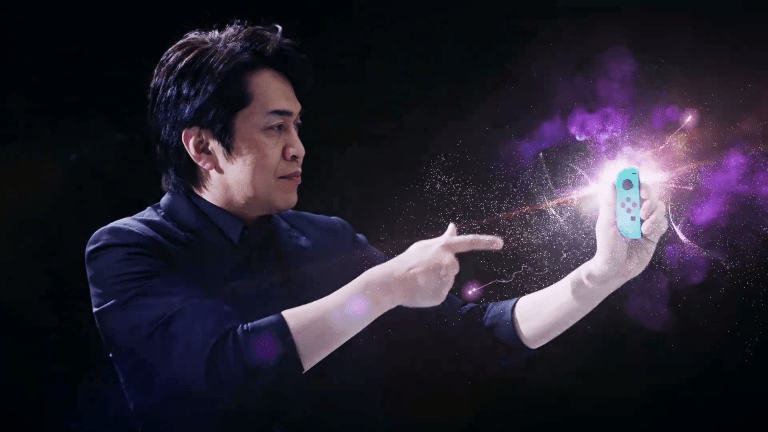

Plot aside, Super Mario Galaxy also refers to Donkey Kong Jungle Beat for a real game design reason. Where the second circumvented the camera problem, the first saw fit to opt for more “spherical” levels, and therefore less subject to framing. Naturally, however, Super Mario Galaxy 2 promised to do an about-face on many of Koizumi’s innovations, both in terms of narrative (the introductory scene almost seems to mimic Rosalina’s book) and in terms of gameplay (Mario’s headquarters is now a means of accessing a more classic map screen). But not all the silver linings: later, Koizumi made progress in the Big N, and today he is a producer of Nintendo Switch, console that Satoru Iwata has not had time to see on the shelves. Besides being his successor in many Nintendo Directs, of course.

Outings with Miyamoto | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

As a protégé of Miyamoto (interpreting his cryptic feedback, made up of sentences often without a subject), Koizumi often draws real-world experience for game design. L’hiking led him to try to amaze the player by replicating impressive scenarios, merging them with accessible gameplay. Creating the main character for him is what takes the most time, as it requires a balance between fun and complexity. More importantly, the plot holds an importance to him that the gameplay only narrowly surpasses. “If you believe my games are something to interact with, you are missing out on immersing yourself in them. I hark back to real life: trekking in the mountains and wondering what’s in that cave – it’s this sense of wonder that I want the gamer to feel.”

Stealthy like Snake, narrative like Kojima | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

In an interview, Koizumi told how much discretion it takes to introduce a minimum of plot in the titles of the Grande N. We propose below the excerpt outgoing.

“Usually [Nintendo] EAD doesn’t focus much on story for its games. I was the one who came up with the plots, since Link’s Awakening. But even then, with all my backstory for Link, the others didn’t seem to care too much. They always said not to push the story too much. So I always try to write one without anyone noticing. For example, I’ve always liked the idea of eavesdropping on another character’s conversation and slowly discovering the story, something I did in Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask. A lot of this came from me, but they are aspects for which Miyamoto was not crazy and, indeed, almost despised them.”

The journey and the destination | In game design school with Yoshiaki Koizumi

Ironically, it was Miyamoto himself who first created a story in video games: in fact, in Donkey Kong, instead of escaping ghosts in a maze or fighting back during an alien invasion, the player’s goal was to save a damsel from a crazed ape. In short, a 1930s short film plot told in pixels. In the same interview, Koizumi sees saving the princess as more of a simple one finish line than a (however basic) narrative pretext. A real texture would add more detail, including a satisfactory resolution. And, therefore, a good incentive to play. Not for this Miyamoto’s style is “wrong” a priori; it’s just about different priorities for the purposes of the player experience.

The kyokan versus the experience

We spoke, first with Miyamoto and then with Kojima, of kyokan: make others share in a sensation, with the intention of arousing empathy. But the kyokan is part of Japanese philosophy; it is not a Miyamoto creation. His vision of the concept, in fact, can be summed up with “we offer players what makes me enjoy”. Kojima’s, on the other hand, focuses on a much more cinematic interpretation of the video game, as a means of conveying (and occasionally manipulating) emotions. Why, then, should Miyamoto and one of his subordinates be poles apart as yin and yang? Yoshiaki Koizumi metaphorically represents the tourist armed with a camera: immortalize every moment to present it again to the amazed eyes of friends. Quite simply, for Miyamoto “it wouldn’t be the same” as experiencing that feeling directly. The difference is all here.

Now it’s up to you to tell us yours: who do you think we’ll talk about the day after tomorrow? Let us know below, and as always, don’t forget to stay on techgameworld.com for all the most important news for gamers and more. For your purely gaming needs, you can instead find the best discounts in digital format on Kinguin.

Leave a Reply

View Comments