“And so it was that the big bad wolf ate the hunter too”: the cruel surprise ending of the game design column is everything for Yoko Taro

If it is true that the arrival of Eiji Aonuma in The Legend of Zelda series has contrasted the oppressive world imagined by Yoshiaki Koizumi, it is also true that our column of game design can end with a similar whiplash: specifically, talking about Yoko Taro. Compared to artists such as Shigeru Miyamoto, Hironobu Sakaguchi, Masahiro Sakurai or even Hideki Kamiya, here we are more on the same wavelength as Hideo Kojima, Hidetaka Miyazaki and Goichi Suda: we are therefore talking about a narrative more cynicism. Having Berserk as a muse is one thing, as seen with Miyazaki’s works; another is to dive headfirst into the psychoanalytic realm of dark works at the level of Neon Genesis Evangelion (deconstruction of the mecha genre) and Puella Magi Madoka Magica (which does the same with the magical girl genre). A way like any other to remind us that August is overIn short.

Flags at half-mast | Game design school with Yoko Taro

Born on June 6, 1970 in Nagoya in Chūbu, Taro Yoko (as the Western reading would dictate, which we have adopted in the previous nine installments on game design) was raised by her grandmother (with a very clear memory of her) due to the long absences of the parents for work reasons. As a young man he learned of an incident that would mark his narrative style: an acquaintance saw one of his friends die from a disastrous fall. The scene, as it was narrated at that juncture, was “horrible”, but with a unexpected comic twist (i.e. a tumescence in an intuitable but unmentionable part of the body). Yoko studied at the Kobe Design University, Kansai, and graduated in March 1994. During her future and unforeseen career in the gaming industry, she would marry a colleague: Yukiko Yokoillustrator for Taiko no Tatsujin and Drakengard 3. We don’t know if the surname is acquired or not, but according to the data found, it is the second case.

The Two Drakengards | Game design school with Yoko Taro

E unexpected, the gaming career, it really was. Despite Yoko Taro’s intentions to do so, within a month of graduating she found a job as a CGI designer for Namco. In 1999 he then joined an offshoot of Sony Computer Entertainment, Sugar & Rockets Inc.then switch to Guinea pig (Ccomputer Afun Viarealizer). Involvement for role play Drakengard by Square-Enix for PS2 started from this context. Takuya Iwasaki was directing until other commitments forced Yoko to take over and help with the script. The changes went close to him, but despite his requests he still found himself in the production of Dragonguard 2. His idea for him was to create an arcade title with dragons in a sci-fi space setting, which is why he found himself at loggerheads with director Akira Yasui. The turning point came with the third game, which was not going to be Drakengard 3. This, however, nobody knew.

Go close | Game design school with Yoko Taro

The initial concept of Drakengard 3 changed to such an extent that, while keeping the same backstory, it was renamed NieR, effectively a spinoff of the series. Despite this, Yoko Taro continues to consider it the third actual chapter. Following the game’s release, with Cavia’s absorption by AQ Interactive Yoko left the company hoping for a freelance career. During this time she helped Square-Enix with Monster × Dragon, to then continue with similar mobile titles. Returning to the main series, after the release of Dragonguard 3 (developed with feedback from players, whose questionnaire responses implied that gloomy stories were the primary source of appeal) “found itself among the jobless”. Hence, a temporary column for Famitsu: “The ill-thinking circle of Taro Yoko”. In 2015 he, his wife Yukiko and screenwriter Hana Kikuchi founded the private company Bukkoro. The sequel NieR:Automata was developed by Square-Enix, but involving PlatinumGames due to Yuki Yokoyama’s hesitation over the first chapter’s low sales.

Memento hikikomori | Game design school with Yoko Taro

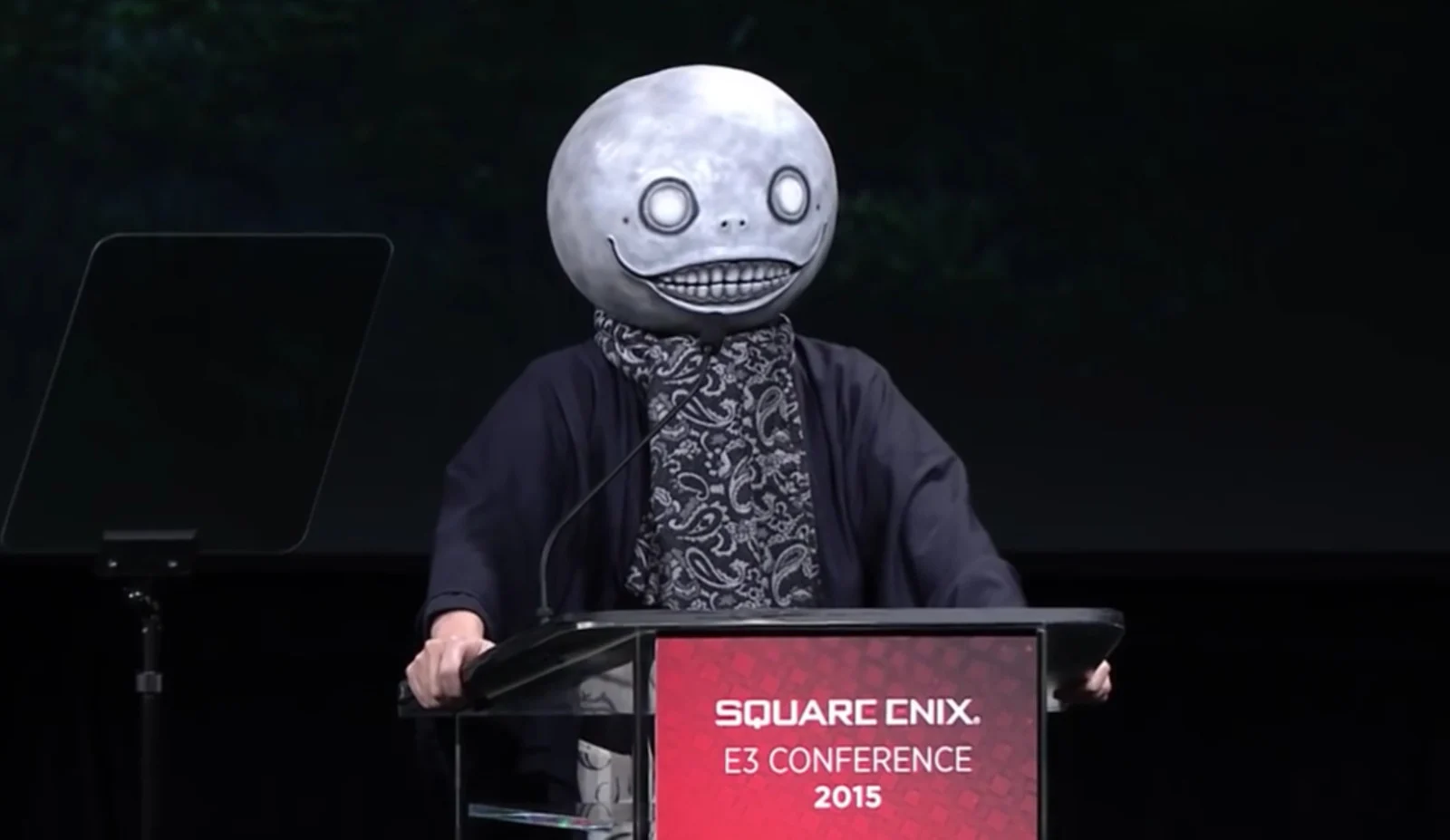

Yoko has never made a secret of hers aversion to sensationalism applied to behind the scenes of video games. The reason, according to what he said about Famitsu, is that according to him the developers are not show people, and that talking about certain technicalities can get boring. When interviewed, he prefers to avoid photos with his now iconic mask (or a theater puppet, in the case of Drakengard 3). He also prefers the brutal honesty when he has his say, as what the players deserve. His games share a dark and foreboding atmosphere, and his writing style is to start with the ending and then reverse, prioritizing key plot points. He loves to experiment with the videogame medium, as he believes that market conventions inhibit the creative freedom of developers. Many games touch his conception of death with the Socratic method (that is, oversimplifying the concept, drawing unexpected answers from mutual feedback).

“Come back here, you cannon fodder full of experience points!” | Game design school with Yoko Taro

To what the protagonist of Drakengard owes his madness? The irony of imagining PlatinumGames during the development of NieR:Automata comes from here. Yoko Taro noticed how insane player performance ratings were based on eliminated enemies (a trademark of Hideki Kamiya) and therefore gave Drakengard a mentally unstable protagonist. Similarly to Goichi Suda, then, Yoko explored the idea of a terrible event caused by two factions convinced they are doing good in Drakengard 3 and NieR, inspired by the war on terrorism post-9/11 for the latter. Yoko Taro’s unconventionality is also seen in the revulsion she feels towards forgettable female characters badly inserted into video games. You have seen it with Furiae in Drakengard and Zero in Drakengard 3, in the latter case opting for the archetype of the former prostitute, almost absent in this medium.

Commitment to outrage

When we started this journey, exactly thirty days ago, we discovered the very foundations of game design with Shigeru Miyamoto, and today with Yoko Taro we discover another point of view. Those who know him closely recognize his cynicism and gentle manners, calling him before anything else an iconoclast. Looking at the industry through the ten names we’ve talked about this month, we’ve seen more ways in which to understand the video game, following or, as the case may be, overturning previously non-existent conventions. At the risk of repeating the farewell seen at the end of the article with Goichi Suda: first pioneers and then revolutionaries. The exchange of ideas, similar to the School of Athens painted by Raffaello Sanzio, is continuous and makes this art form ever more dynamic. “Our” is a evolutionary path which we intend to follow very, very closely.

Now it’s up to you to tell us yours: would you like a second “game design month”, perhaps next August? And with what names? Would you like more western authors next year? Let us know below, and as always, don’t forget to stay on techgameworld.com for all the most important news for gamers and more. For your purely gaming needs, you can instead find the best discounts in digital format on Kinguin.

Leave a Reply

View Comments