July 27, 1982, the publisher Atari he was jumping for joy at having just managed to get the right to develop and market a videogame transposition of ET the extra-terrestrial, a famous feature film signed by Steven Spielberg who at that moment was making a splash at US ticket offices. No, limiting the impact of the film to a mere question of the box office is an understatement, the film had such a resonance that it was even screened at the United Nations Organization, a venue which for the occasion also proceeded to award the Peace Medal. to its director.

Atari had an unsinkable brand on his hands, pure gold, plus he had managed to recruit Howard Scott Warshaw for the occasion, a highly esteemed game designer who had already worked alongside Spielberg and who could boast the utmost confidence of the master of Cinema, nothing could have gone wrong. Or so one would think if history had not proved otherwise, if ET had not been such a flop to be considered the first real cause of the collapse of the gaming market in 1983. But how could such a virtuous project have fallen so low as to cause an economic crisis to the entire digital entertainment sector?

The gaming world that paved the way for ET and Atari

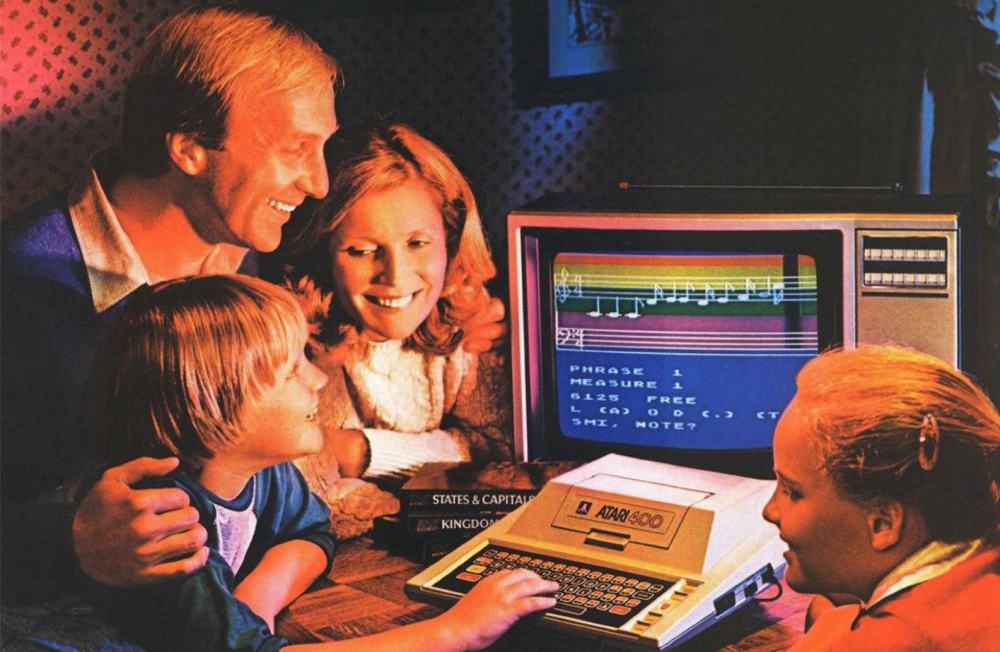

The so-called “video game crash” of 1983 was a real turning point for the video game universe. In the space of a few years the industry has been dramatically revolutionized, however to understand the failure of Atari we must remember that at the time digital entertainment was not considered a trifle for children, far from it. Originally, the cabinets entered everyday life alongside the timeless pinball machines, therefore video games were mostly considered bar entertainmentsomething to hang out with between one beer and the next after having unplugged from a hard day’s work.

Consumption habits have therefore changed, hybridized, and the advent of home consoles has ensured that the videogame sphere expanded to include the entire family within it. Women, men, girls and boys: everyone was greeted by the electric embrace of Atari and its competitors. Videogames were practically lived on a par with board games to be enjoyed convivially and the market did nothing but grow and grow, unconsciously aiming at collapse.

Classic videogame advertisement from the seventies.

Classic videogame advertisement from the seventies.

Close to 1982 the industry of the sector was subject to a multifaceted set of pitfalls: personal computers were starting to enter the homes of users, the gaming device sector had exploded to saturation and the development of video games was no longer a ‘ exclusive of distributors. At the time, The New York Times had defined the situation with the colorful epithet of “video game sales war“, Outlining in his article the existence of a bloody” war “in which any strategy was legitimate.

The “liberalization” of software development and the companies’ inordinate lucrative ambitions quickly translated into a supply of goods that vastly outstripped actual customer demand. Even more, a large portion of the video games released had been improvised by inexperienced game designers, hastily recruiting to participate in a digital gold rush, with the result that store shelves were flooded with immense amount of computer junk.

The genesis of an unwelcome alien

In this ultra-competitive environment, Atari was not doing brilliantly. A few years earlier, in 1979, some of his dissatisfied programmers had set up their own business and founded a company known as Activision, who gave birth to Pitfall in 1982! demonstrating in fact that an independent developer was easily able to wear down the monopoly of those traditional distributors who were now more driven by the need to do business than by the desire to innovate their offer.

Desperate to stand out from the competition, Atari therefore focused on marketing brands known to the general public. In 1982 the selection had fallen on two brands in particular: Pac-Man ed ET the Extra-Terrestrial. The Pac-Man transposition for the Atari 2600 was released in March of 1982 and, despite having sold more than seven million copies, was crushed by critics and gamers around the world due to its abominable performance. Many returned the game and asked for a refund, however the real damage suffered by Atari was that received to reputation. The public, who had always considered the company a bulwark of videogame perfection, finally began to perceive a certain diffidence towards it.

ET the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) per Atari 2600.

ET the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) per Atari 2600.

A few months later, ET could have represented an important ransom for the publisher, however the management of Atari imposed on Warshaw a stifling roadmap: the man would have to finish the development of the game in time for it to be in the shops by Christmas time, meaning everything had to be ready within about five weeks. History teaches us that things did not go in the direction that entrepreneurs had naively hoped for.

ET the Extra-Terrestrial was graphically disappointing, muddled in purpose, and extremely monotonous. Warshaw’s creature was not entirely without merits, but these were well hidden in a product that is at least raw and that today is often listed in the lists of the worst video games ever released on the market. Regardless of the value of the object itself, the stock represented yet another disappointment of a market that would soon collapse.

The new world blessed by Nintendo

The fiscal year of 1983 had resulted in a loss of $ 536 million for Atari. In the years immediately following the company was spun off from the parent company, Warner Communications, and was sold in part to Jack Tramiel, founder of the competitor Commodore International who recently became his own, and in part to the arcade giant, Namco. An unknown number of video games and accessories dedicated to the Atari 2600 was therefore disposed of well and best in the New Mexico deserta place that still hosts those cartridges and consoles that the market had repudiated, including ET.

For better or for worse, the crack that hit the entire industry in 1983 has shaped today’s videogame imagery. In an attempt to revive the supply chain, the Japanese Nintendo has in fact decided to intervene in the sector with a marketing vision to say the least overwhelming: instead of creating a device designed for the whole family, the Japanese giant has preferred to focus all promotional efforts on to pound male children.

No longer considered an entertainment tool for any age, consoles began to be marketed as hi-tech toys, with the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) quickly making it to the 1985/86 childhood Christmas lists. Atari and ET the Extra-Terrestrial have therefore not really destroyed the video game sector, however they represent the most prominent element of a historical episode in which greed has launched an entire sector in a cycle of death and resurrection that can be read at hindquarters with a warning tone.

The industries had then abused the trust and patience of consumers, placing their speculative aims before the reciprocity of the seller-customer relationship, all in a landscape in which entrepreneurial competition was strongly focused on maximizing the profit margins that were obtained from services. increasingly poor. ET had the misfortune of appearing in the wrong place and at the wrong time, however it is easy to see that his mythological figure embodied more complex criticalities, criticalities that were systemic and perhaps still are.

ET cartridges unearthed in the New Mexico desert.

ET cartridges unearthed in the New Mexico desert.

Source

Intervista a Howard Scott Warshaw

Leave a Reply

View Comments