Welcome back to our weekly appointment with In the mood for East, a column entirely dedicated to oriental cinema. Today we are going to talk to you about Seijun Suzuki’s The Butterfly on the Viewfinder

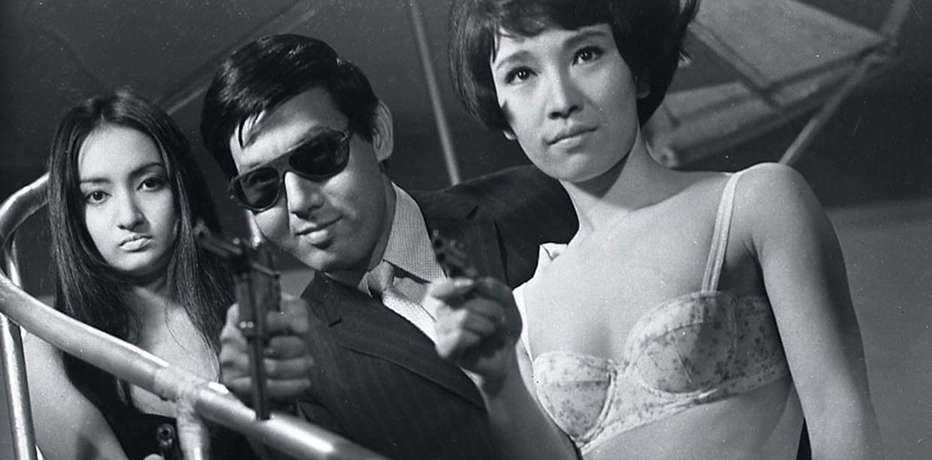

You are in a Tarantino movie. You’re in the car, a cool soundtrack starts, the violence is about to explode. No, sorry. You are in a Hollywood noir film from the 1940s. Black and white, as per tradition. There is the smell of sex, gunpowder, whiskey and cigars as if it were raining. No, it doesn’t work: you could be James Bond: license to kill, action, danger and beautiful women by your side. But, wait a moment: there are almond eyes. Found it! You are in a classic yakuza movie, how could we not think about it before?

But no! You are like every Monday on In the mood for East, our column dedicated to Asian cinema of all times and all genres. Perhaps the coordinates have led you a bit astray, but you will see that once you have tackled today’s unsettling film you will be able to recognize all the elements mentioned. Today we will focus on The butterfly on the viewfinder, 1967 film noir / gangster directed by Japanese director Seijun Suzuki. The impact that this work has had – and continues to have – on world cinema is truly incredible. The butterfly on the viewfinder takes and gives, cites and is a source of citation (Park Chan-wook, Jim Jarmusch, Wong Kar-wai, Jhon Woo).

Seijun Suzuki, who passed away in 2017, was in trouble because of his job, even going so far as to sue his production company (Nikkatsu, an integral part of the history of Japanese cinema, founded in 1912), guilty of having fired him for the incredible flop obtained, from critics and audiences. Forty films in eleven years weren’t enough to save him from that failure. The case raised led him to become a political director, both for purposes and for the events related to him. It will take a few decades for the film to be re-evaluated not only at home, but all over the world, making Suzuki a real hero of the counterculture. Now we are finally ready to talk about a much discussed and singular work.

Plot and trailer | The butterfly on the viewfinder

Goro Hanada (Joe Shishido, an actor who even had his cheeks plumped to appear “tough”) is a professional killer, number 3 in the criminal organization he belongs to. Unyielding, professional, with a fetish for the smell of rice. The tasks he must complete are always difficult, but never as difficult as the one entrusted to him by Misako (Annu Mari), a mysterious woman obsessed with death, with whom he falls in love. His task is in fact to kill a stranger who investigates the activities of the organization. However, a butterfly placed on the sight of his rifle will lead to a fatal error.

For the killer’s code, this mistake will have to be paid for with life. First Hanada will be threatened by those closest to him, including his wife (Mariko Ogawa) and the charming Misako, then he will have to contend with “the ghost” (Kôji Nanbara), the number one killer of the gang.

Anarchy in entertainment cinema | The butterfly on the viewfinder

I believe that there is no fixed space and time in a film. […] In my films, spaces and places change. For example, in one shot there are two characters, and in the reverse shot of one of the two, the latter is in a totally different place. The film, however, does not lose its meaning. In addition, through editing the director can change the tempo to his liking. […]. I think this is the strong point of entertainment cinema. Anything can be done, as long as it makes the film interesting. This is my theory of the “grammar of cinema”.

Suzuki’s is a anarchist cinema, In the true sense of the word. An avant-garde cinema, which thrives on intuition, very fast, not preconceived. Suzuki starts from b-movies and nevertheless arrives at a genre cinema, but grafted it with creativity and subversion. The French and American noir, but also the yakuza movie, are borrowed to be completely annihilated by his skilled and unscrupulous hands. In short, Suzuki raises them with everything that makes cinema alive. In doing so, he raises himself to cult author, despite his many times overt little ambition on an artistic level.

Yet thirty-four years later, Suzuki presents its sequel at the Venice International Film Festival. Pistol Opera demonstrates how The Butterfly on the Viewfinder was not just a flash of creative madness in its author’s career. Suzuki once again proves to be capable of creating something “alien” from everything else.

The decline of a gangster | The butterfly on the viewfinder

It’s strange to think how the fate of the protagonist of The Butterfly in the Viewfinder intersects with that of its creator, both destined in a sense to an involution. The former must surrender to imminent death for a mistake made, the latter must surrender at the end of his career (Suzuki was not allowed to shoot for ten years) due to a “wrong” film. To the detriment of the film’s failure, at that moment the cinematographic and genre language was completely unhinged. Just think of the role of the gangster: the protagonist is initially presented as whole and loyal to duty (even if dampened by his fetishist peculiarity), to then undergo a irreversible decline, intoxicated with alcohol and sex.

Everything appears deformed and deforming: the prevailing jazz, the black and white that caresses and makes sharp faces, the daring shots. But above all the assembly, which makes almost rambling jumps (the film was edited in just twenty-four hours) making the events anything but linear. And to think that today pulp cinema has made it one of its main characteristics.

Surreal, perhaps too late for the sixties, a distorted and daring work.

Conclusions

“I make films that don’t make sense.” Perhaps Suzuki was too merciless towards himself, perhaps there was a grain of truth in his words. Who knows. But having influenced a generation of great filmmakers will mean something. Just as it influenced a genre, that of the yakuza movie, to the point of completely subverting its rules. From The Butterfly on the Viewfinder onwards, Suzuki’s cinema took a turn – and not just because of his forced pause. Japanese cinema itself was undergoing an upheaval, as was the language of cinema. And maybe it wasn’t just a matter of luck. Seeing is believing.

Keep following ours specials on cinema and TV series on this page, with new appointments every week!